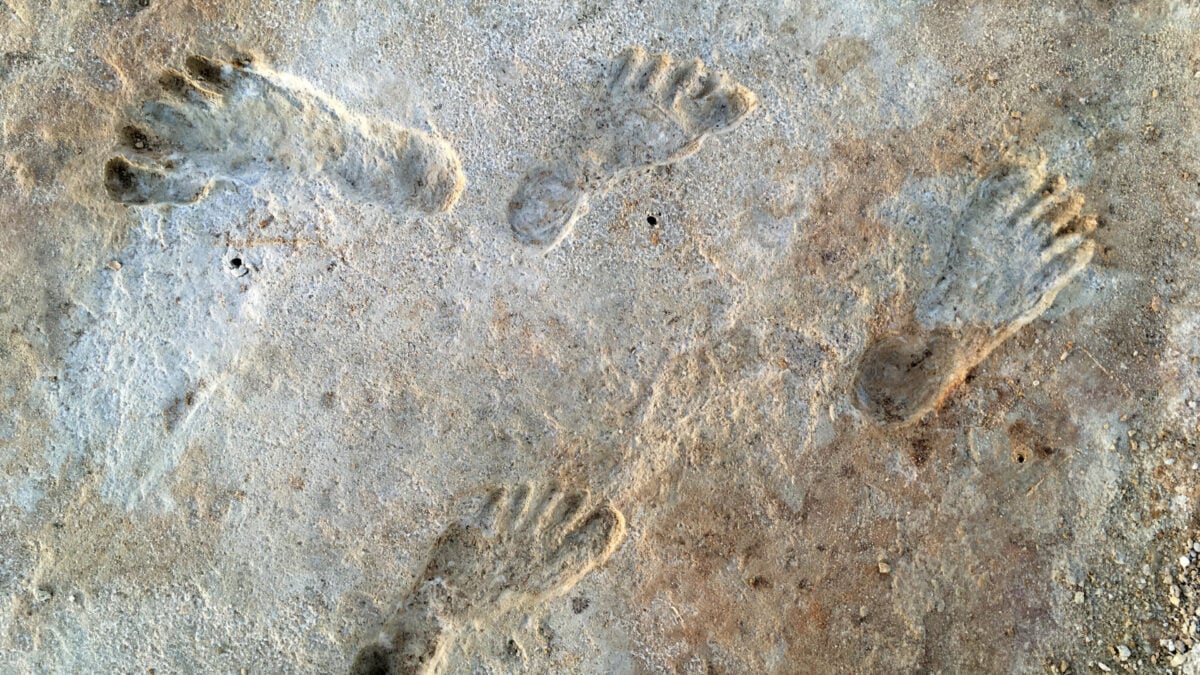

Recent Research Supports Disputed Assertion of 23,000-Year-Old Human Footprints Found in New Mexico

In 2021, researchers working in New Mexico published a paper that contributed to what remains one of the most controversial topics in American archaeology. The study describes human footprints in White Sands National Park dating to between 23,000 and 21,000 years ago, making them the oldest-known footprints in North America. This challenges long-held beliefs that the first North Americans were the Clovis people—named after artifacts found near Clovis, New Mexico—who arrived between 13,000 and 13,500 years ago during a relatively warm window near the end of the last Ice Age.

Because footprints can’t be directly dated, researchers estimated the age of these trace fossils—between 23,000 and 21,000 years old—by radiocarbon dating seeds found in the layers above and below the tracks. While critics continue to argue that the ancient seeds do not accurately represent the site’s age, new research published earlier this week in the journal Science Advances adds further support to the original findings. As such, the seeds of the aquatic plant Ruppia cirrhosa are making another appearance at center stage in this debate.

“The issue of the arrival of the first Americans has long been contentious and the record from the White Sands locality generated considerable debate focused on the validity of the dating,” wrote the researchers in the new study, including University of Arizona archaeologist and geologist Vance Holliday, a co-author of the 2021 paper. “This paper presents the results of an independent stratigraphic study with new associated dates, largely from a third source of radiocarbon that supports the initial dating.”

In short, Holliday and his colleagues radiocarbon-dated new organic material, including Ruppia seeds, from new geological layers associated with the footprints. The team’s new age estimate for the layers containing the footprints is between 23,000 and around 17,000 years ago, which overlaps with the original estimate of between 23,000 and 21,000 years ago. Radiocarbon dates of organic-rich sediments in one of the study areas, Gypsum Overlook, align more closely with the original estimate, yielding between around 22,400 years ago and 20,700 years ago.

If the footprints are 23,000 years old, that means humans arrived in North America before the Last Glacial Maximum—when ice essentially created a barrier from the North Atlantic to the North Pacific coasts around 20,000 years ago. Even if the footprints are just 17,000 years old, that would still suggest that humans arrived in North America before the end of the last Ice Age around 11,700 years ago.

“This is a paradigm shift in the way we think about the peopling of the Americas, and human evolution more widely,” Nicholas Felstead, a researcher from Swansea University’s Department of Geography who did not participate in the study, told Gizmodo in an email. “This all but confirms multiple migration routes into the Americas, other than just the ice-free corridor around 14,000 years ago.” Early humans likely reached the Americas by island-hopping along the Bering Sea and Pacific coast, crossing the massive ice sheets of the Northern Hemisphere, or possibly drifting across the Pacific or Atlantic Oceans, Felstead explained.

According to Karen Moreno, a paleobiologist at Austral University of Chile, the new research aligns with evidence from South American sites such as Monte Verde, Pilauco, Pedra Furada, and Arroyo del Vizcaino. The evidence from these sites suggest a human presence dating back 16,000 to 20,000 years ago, if not 30,000 years ago. “South American evidence has certainly been overlooked, and I’m happy to know that North American work is finally pointing out to the direction our research in the South was supporting,” Moreno, who wasn’t involved in the new study, told Gizmodo in an email.

A study published in April, however, seems to call into question—once again—the validity of radiocarbon dating organic matter from the White Sands site. The main point of contention centers on what’s known as the hard water effect. The effect occurs when aquatic plants like Ruppia draw carbon from groundwater, unlike terrestrial plants, which absorb carbon from the atmosphere, David Rachal, a geoarchaeologist with Vieja Consulting and a co-author of the April study, explained to Gizmodo in an email.

The carbon in groundwater consists of very old dissolved limestone, which makes aquatic plants appear much older than they actually are in radiocarbon dating. As such, the hard water effect is “baked in” to both the Ruppia seeds and other organic material from the mud layers in question, Rachal explained.

“According to their model, if the Ruppia grew within the site under these uniform-like conditions, shallow water, very well aerated, then the hard water effect is not a problem,” he said. Rachal and his colleague’s model, however, indicates that the plant did not grow at the site, but rather washed into it. “There’s zero physical evidence that the plant grew within the site. And if it didn’t grow within the site, the hard water effect is still there.” As such, any other samples that match the Ruppia seeds dates are also problematic, he added.

Even without considering the hard water effect, 23,000-year-old footprints still raise more questions than it answers, according to Ben Potter, a University of Alaska Fairbanks anthropologist who also did not participate in the study. Namely, because they left no other known traces for 10,000 years. “We need actual human-produced artifacts to understand the identity, behaviors, and potentially fate of these populations,” he told Gizmodo in an email.

Ultimately, today’s study represents the most recent volley in the highly contentious first-Americans debate. The ball is once again in the opposing side’s court, and I’m sure their response will not take long.